Welcome to my message board.

New member registration has been disabled due to heavy spammer activity. If you'd like to join the board, please email me at MaxDevore at hotmail dot com.

New member registration has been disabled due to heavy spammer activity. If you'd like to join the board, please email me at MaxDevore at hotmail dot com.

Comments

Co-editor Stephen King supplies the introduction, which addresses general fears of flight as well as King's own more personal ones. As is almost always the case with his introductions, King is very engaging here. He also supplies brief introductions to each of the following short stories, which is a nice bonus.

"Cargo" (E. Michael Lewis, 2008)

This one is about a team of servicemen hauling a plane full of corpses back home from Jonestown. Weird things either do or don't begin happening.

I'm not sure there's an actual story here, but this is a good intersection of what-if with real life; the atmosphere is strong, and good creeps are dispensed.

"The Horror of the Heights" (Arthur Conan Doyle, 1913)

Lovecraftian fiction ... from a time before Lovecraft! In this story, an aviator goes into the skies and finds something horrible. Parts of a journal on the subject are later found and marveled at.

I think this was the first thing I've ever read by Doyle. I found it to be solid and imaginative. It didn't blow me away, but I give it a definite thumbs-up.

"Nightmare at 20,000 Feet" (Richard Matheson, 1961)

An obvious classic, but (to my discredit) not one I'd ever actually read. For that matter, I've never even seen the original Twilight Zone episode; the remake in the movie, yes, but not the original.

I know, right?!?

Anyways, the original story, in which a man sees a menacing figure on the wing of a commercial flight mid-air, is an excellent depiction of madness.

Or is it?

Either way, who could refuse to take action in such a situation should the need and opportunity to do so arise? And if it the narrator IS crazy ... boy, that relatability of the need for action makes everything even scarier than it already was.

"The Flying Machine" (Ambrose Bierce, 1899)

I didn't get it.

I'm sure I'm missing something; I'm less sure I care.

"Lucifer!" (E.C. Tubb, 1969)

I'm not going to say anything else about it, other than to say that I found this one to be great. It's a science-fiction story first and foremost, I think (and not the only one in this anthology); but the horror, when it arrives, packs a serious punch.

"The Fifth Category" (Tom Bissell, 2014)

This one reads almost like it is in part an homage to The Langoliers, except what's going on here really does seem to involve the government scooping someone off a flight and trying to convince them they're still there.

Bissell provides a lot of material about '00s-era Guantanamo-esque torture concerns, and I wonder how much of that is accurate? I hope not much; I fear differently.

Excellently-written and very involving stuff. According to Bev Vincent's afterword, it was Owen King who suggested this one for inclusion. Good suggestion!

"Two Minutes Forty-Five Seconds" (Dan Simmons, 1988)

This was, I believe, the first thing I've read by Simmons. It doesn't deter me from wanting to read more, but it doesn't amp the desire up any, either.

Guy is on a rollercoaster, except it's actually a plane that is about to crash, seemingly because he put explosives on the wing, seemingly because of some incident in the past? I think?

I feel like I probably didn't pay sufficient attention to this one, but I wasn't in a mood to do so, and so I didn't. Sorry about that. I'd still love to read Hyperion and/or Carrion Comfort someday!

"Diablitos" (Cody Goodfellow, 2017)

This one didn't do much for me; it struck me as not much more than an excuse to have a lot of scenes in which people puke bugs. This is probably an instance of me being uncharitable. I mean, lookit that photo above. No way that guy doesn't deserve my respect. I can practically hear the theme music from The Dunwich Horror as I look at it! Anyways, bugs are puked in "Diablitos," and it's not a bad story at all.

"Air Raid" (John Varley, 1977)

This one, I loved. I'd never read anything by Varley, but this story -- which he later rewrote in novel form as Millennium (not to be confused in any way with the Chris Carter television series, although the novel itself was adapted into a 1989 movie of the same name) -- is a beaut.

It's told from the point of view of Mandy, a member of a "Snatch Team" operating from a future Earth. The people of that time have mostly succumbed to a crippling genetic mutation, but have figured out how to open portals into the past, and send Snatch Teams back to rescue passengers from airplanes that are fated to crash. They can't change the past in any way; they can only exploit things that happened.

I may have to get a copy of the novel and read it; I'd be happy to spend more time in this story.

I used to see copies of this all the time; it must have sold well. I never got one, though. What a fool I've been!

Yep, pretty sure I'm gonna track one of those down. This story reminded me of the years in college in which I read quite a lot of science fiction (though never enough); it reminded me a bit of Alfred Bester and a bit of Cordwainer Smith, to be specific. Not bad things to be reminded of.

"You Are Released" (Joe Hill, 2018)

It's about a routine flight from Los Angeles to Boston during which contact is lost with Guam around the same time a "flash" is observed from that direction. Not by the airplane, you understand; just in general, as reported to the pilot from the ground. This story clearly takes place in some sort of weird future where Guam has been threatened by North Korea, and in which things could potentially escalate REAL quickly if there were any sort of reason for them to. That Joe Hill; he's a master fantasist.

The story bounces back and forth between the perspectives of a set of characters, and gut-churningly well-written. Ol' Joe King may have himself a future.

In his introduction, Big Steve King confesses that Joe Hill is his son, and says he couldn't be prouder of the relationship.

"Warbirds" (David J. Schow, 2007)

Schow's story involves a man whose father has died. He is visited by a man who flew missions with his father during World War II; this man, Jorgensen, tells the son about his belief that the Allied and the Axis weren't the only powers in the sky during that war. (The main character in Doyle's "The Horror of the Heights" could relate.)

It's a well-written, involving story that makes one feel as if one is aboard the bomber plane Jorgensen describes; and the end of the story is strong, which is always a plus.

"The Flying Machine" (Ray Bradbury, 1953)

This one is a parable-esque tale about the emperor of China, who sees a man flying in the air with constructed wings and calls him down to have a little talk about it. Good stuff from a guy whose ability to write good stuff is considerable.

I am reminded of my need to go on a Bradbury binge. This story made its intial appearance in his collection The Golden Apples of the Sun, which I've owned a copy of for, like, twenty years and STILL have not read.

Goddamn, I suck.

"Zombies on a Plane" (Bev Vincent, 2010)

Vincent's contribution is not a new tale written expressly for this anthology, though it is probably natural to assume so (given that the other co-editor, Stephen King, placed a new tale within it). It's shorter than I was expecting, and less trashy. I didn't really connect with it until the end, at which point I got a big ol' grin on my face.

I should probably say something more about it than that, but this seems like a story that ought to be read, not summarized.

"They Shall Not Grow Old" (Roald Dahl, 1946)

One of these days, I'm guessing my blogger's eye will turn to him in a major way. That'll be cool; I've not read most of his stuff in decades, and I've read very little of his writing for adult readers. Such as this very story!

Which, obviously, I have now read. It's very good, and shares with his writings for children a certain whimsicality that persists in the face of adversity and/or outright horror. It's about some British fighter pilots, one of whom goes missing and is presumed dead only to turn up again two days later, convinced he's only been gone an hour. What happened to him?

Read the story and find out.

"Murder in the Air" (Peter Tremayne, 2000)

This one is a locked-room murder mystery set on an airplane in the middle of the flight. Guy gets dead -- apparently via a gunshot -- in the bathroom, and no weapon is found when the door is broken down.

Good setup; good execution.

This isn't really my genre, per se, but I enjoyed the story, and it reminds me that I'd like to read some Agatha Christie one of these days. I saw the seventies films based on Murder on the Orient Express and Death on the Nile last year, and very much enjoyed them. Which has nothing to do with Peter Tremayne, except that his story fits nicely into those parameters; not a bad thing to be able to boast.

"The Turbulence Expert" (Stephen King, 2018)

"The Turbulence Expert" is, of course, the primary reason why I bought Flight Or Fright. This perhaps creates the expectation that it will be my favorite story in the book. And the verdict on that: nope. That'd handily go to "You Are Released," with the Matheson and Varley stories as runners-up.

Which is not to say that "The Turbulence Expert" is bad. Nope: it's good; not one of the better recent King stories, I'd argue, but good.

It's about a guy who works as a "turbulence expert," accepting commissions from an unknown "facilitator" who places him on commercial flights which are fated to experience clear-air turbulence. The expert's job: save the lives of every soul onboard by...

Well, read the story and find out.

"Falling" (James Dickey, 1981)

"Falling" is a poem based on a true story about a stewardess who is sucked out of an open door. I'd read this before, in college, back when I was a more learned man than the one who mostly now watches Tobe Hooper movies and stays up past dawn.

King acknowledges in his introduction that not everyone is into poetry, and I'm guessing that the placement of "Falling" is a tacit admission that it's a bit like the credits of a movie in that most people are going to get up and leave.

It isn't exactly the most penetrable verse ever put to paper. I freely confess that I simply wasn't in the mood to bite down on the work long enough to get the flavor of it; I remember that being the case the first time I read it, too. I haven't been in that mood in about two decades, and that's a fault in my character, not a fault in the poem.

That said, Dickey has no interest in making it easy on anyone, so casual readers -- which, let's face it, is the vast majority of King readers (which, let's face it, is the vast majority of Flight Or Fright readers [and which, let's face it, is entirely understandable on all counts]) -- are statistically likely to get to this and just grey out.

*****

Bev Vincent provides an afterword, including telling the tale of how Flight Or Fright came into being. It was Stephen King's idea, pitched to Vincent and to Cemetery Dance publisher Richard Chizmar around the time of the premiere of the Dark Tower movie. Vincent was tasked with finding the majority of the tales; King would write an original and then introduce each. Vincent found the rest either through prior knowledge or internet research (including Facebook suggestions).

He also points out some interesting resonances the anthology shares with King's novel -- Vincent calls it a novel! (I've been saying it is for years) -- The Langoliers. For example, John Varley is namechecked in that story, and there's a character who treats the entire situation like it's a locked-room mystery (kind of like the Tremayne story). Plus, Jonestown -- a featured component of the E. Michael Lewis story -- is mentioned.

Vincent's take: it all feels like it was meant to be.

All things considered, it's a very good collection of fiction, with the two original tales proving to be well worth the read. Not that there was much doubt on that score; but still.

Stephen King is afraid of flying, as he makes abundantly clear in the introduction to this anthology, categorising it as an activity with “all the charm and excitement of a colorectal exam”, and never mind all those statistics showing how safe air travel is compared to other modes of transport. Flight or Fright contains sixteen stories and one poem. Two of the stories, by Joe Hill and King himself, are original to the collection, while the earliest of what we have on offer, Ambrose Bierce’s flash fiction from 1899, predates powered flight itself. King also provides story notes for each literary gem, while co-editor Bev Vincent in his afterword relates how the anthology came into existence, among other things.

Opening story by E. Michael Lewis is told from the viewpoint of a US loadmaster who, in lieu of his usual ‘Cargo’, ends up with the unenviable task of shepherding the dead bodies of children back from Jonestown. There are hints of the supernatural to the story, but hints is all they are, with the real thrust of the narrative having to do with men under pressure in an extreme situation and how they can become unnerved, even the most professional. It is an unsettling story primarily because it highlights the evil and inexplicable acts human beings are capable of. We have an outré entity in ‘The Horror of the Heights’ by Arthur Conan Doyle, a tale from the early days of manned flight, when heroic aviators competed to attain ever greater altitudes. In this story one man has a theory about what may exist at certain heights. While it remains a gripping read, the backdrop to the story has already been rendered null. The joy here is in reading of the aviator’s exploits, seeing the clues planted in the text as to what may exist up there, and the final, inevitable revelation as to the horror of the heights.

Perhaps the most famous horror story ever written on the fear of flying, Richard Matheson’s ‘Nightmare at 20,000 Feet’ picks up on the idea of gremlins with a protagonist who believes that he sees a creature on the wing of the plane in which he is travelling, and that it intends to cause a crash. Wilson is unable to convince anyone else of the truth of the situation, is just another man afraid of flying who is willing to cause a scene, and the beauty of the story lies in his descent into madness and the ambiguity with which Matheson infuses the narrative, so that we can never really be sure to what degree the things he is seeing are real or simply the hallucinations of a frightened mind.

Ambrose Bierce’s one pager ‘The Flying Machine’ is more about human gullibility than manned flight, with people willing to invest in something as fanciful as the titular flying machine despite all the evidence that it is a very bad idea. It’s a neat idea that doesn’t outstay its welcome. In ‘Lucifer!’ by E. C. Tubb a man steals a time travel device from some future tourist, and though he can only go fifty seven seconds into the past it is enough for him to indulge all his vices, including gambling and murder. Finally he gets hoist by his own petard thanks to an unfortunate incident with an airplane. There are a lot of good ideas here, the story rich in invention and showing how this very limited form of time travel might be made to work, though ultimately it is a story about a bad lot getting his much deserved comeuppance, and as such it pleased me very much. An apologist for state sponsored torture gets on board the wrong plane in Tom Bissell’s ‘The Fifth Category’ and, like the protagonist of the previous story, ends up on the rough end of poetic justice. Bissell does a good job of critiquing American policy on the subject of torture and, in the character of John, provides us with an eloquent spokesperson, albeit one who lacks the self-honestly to see what he really is, with his love of putting things in compartments and thus enabling himself to pardon and justify the inexcusable. The telling is calm, but in the final analysis this is a very angry story, and rightly so.

A guilt ridden man seeks redemption of a sort in ‘Two Minutes Forty-Five Seconds’ by Dan Simmons, a bright, short story that effortlessly blends together guilt and bad memories, cleverly conflating the crash of a Gulfstream jet with the image of a rollercoaster ride into oblivion. Cody Goodfellow’s ‘Diablitos’ has a man who smuggles stolen cultural artefacts back into the States become the victim of an ancient curse, with things going very wrong on board the plane he takes. It’s a familiar plot, but made special by Goodfellow’s epic writing style and the horrific images of plague and disaster with which he fills the tale. Time travellers from a post-apocalyptic future seek to save the remnants of mankind by stealing people from doomed airplanes in ‘Air Raid’ by John Varley, another story with a science fictional twist and a wealth of incidental invention to carry us through to the bittersweet end note.

One of two previously unprinted stories, Joe Hill’s ‘You Are Released’ was my personal favourite. It is told from the viewpoint of passengers and crew on board a plane that is in the air when what appears to be a nuclear war breaks out. Hill captures perfectly the tone of voice of each member of his diverse cast, their growing sense of panic as events unfold and it becomes obvious that this is not an exercise or a false alarm. It is, out of all these stories, the one that feels most pertinent to the world as it is today, the story that has the greatest chance of coming true, and all the more unsettling for that. From strongest story to the one I felt was the weakest with ‘Warbirds’ by David J. Schow. A man whose father served in the USAF during WWII seeks out a member of his father’s old crew to verify an “urban” legend that has haunted him. There’s a wealth of detail here, and it was made all the more interesting for me personally in that the air crew operated out of a base in my native village of Shipdham, and yet in among all that detail it felt very much that Schow had lost sight of his goal, so that at the end I wasn’t much clearer about the point of it all than I was at the beginning.

Ray Bradbury’s ‘The Flying Machine’ is an elegant fable set in ancient China, but at its heart is a harsh moral lesson about the uses to which new technology will be put, the beauty of the words and the underlying sense of sorrow at what takes place demonstrating Bradbury’s oeuvre at its very best. ‘Zombies on a Plane’ by Bev Vincent does pretty much what it says on the tin, as a group of survivors try to escape the zombie apocalypse that has engulfed the civilised world by taking to the skies in a plane. This is a tense, cinematic tale, one that brings to mind the remake of Dawn of the Dead, but ends with a reminder that we always carry the seeds of our own destruction with us, that fate is a hard and uncaring taskmaster who’ll catch us on the way out if he misses us on the way in. Set in WWII, ‘They Shall Not Grow Old’ finds Roald Dahl in a bittersweet mood, his explanation of what happened to a missing airman presenting us with a vision of a post-death gathering of slain pilots, a hint at something truly celestial, a brotherhood that endures beyond death and eclipses mortal rivalry.

Peter Tremayne’s ‘Murder in the Air’ presents us with a variation on the locked room murder mystery, a dead businessman found in an aircraft toilet. Fortunately criminologist Gerry Fane is aboard the plane to cross question the suspects and come up with an explanation for the seemingly impossible crime. Engrossing and thoroughly entertaining, this had about it the feel of a cosy detective story, but one decked out in modern technological trim. The protagonist of Stephen King’s tale is ‘The Turbulence Expert’, employed by a mysterious authority to travel on planes for reasons that become horribly obvious as the story unfolds. It’s a novel idea and developed with King’s usual flair and gift for making the impossible sound not only credible but eminently likely. Nor does the author stint on the horror of the situation, as his hero’s “gift” hinges on his ability to visualise and live through plane crashes. Finally we have prose poem ‘Falling’ by James Dickey, which is based on a true story and gives us a stream of consciousness account of the last moments of an air hostess who has been sucked out of a plane at 33,000 feet up. It is a powerful piece, made all the more so by the vividness of Dickey’s imagery, and the at times almost erotic manner in which he depicts his character’s plight.

Overall this was an excellent anthology, one that captured the very best in airborne thrills and spills, but it probably won’t find an audience among those intent on convincing us that it really is more dangerous to travel by car, or be showing up on the bookshelves in airport stores any time soon.

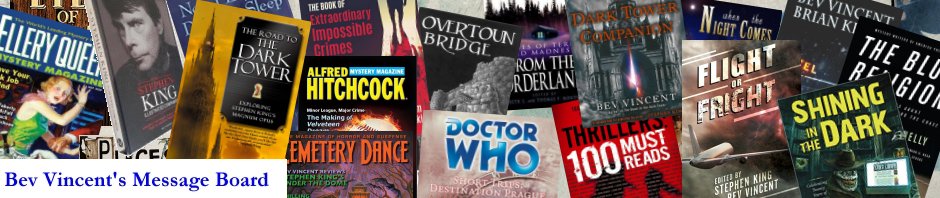

Stephen King has long been considered a master of the horror and suspense genres, penning such masterpieces as It, The Stand, Misery, and Carrie, among many others. In Flight or Fright: 17 Turbulent Tales, Bev Vincent describes in the afterword that King approached him and Richard Chizmar, founder of Cemetery Dance Publications and a master of suspense in his own right, at a diner about the creation of an anthology about the terror of flying.

King and Vincent would go on to collect and edit this anthology, including tales written in an era when flight was in its infancy, to more modern yarns. They also included original stories of their own.

Perhaps the greatest attribute of the audio-version of the anthology is the reading of the introduction to each tale by Mr. King himself. Anyone who previously listened to On Writing will be thrilled to hear the master of horror lending his vocal chords to another great work.

The authors who contributed to this anthology, besides King and Vincent, include Joe Hill (son of Mr. King), Richard Matheson, Ray Bradbury, Roald Dahl, Dan Simmons, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Michael Lewis, Ambrose Bierce, E.C. Tubb, Tom Bissell, Cody Goodfellow, John Varley, David J. Schow, Peter Tremayne, and James L. Dickey.

The plethora of narrators include Stephen King, Bev Vincent, Norbert Leo Butz, Christian Coulson, Santino Fontana, Simon Jones, Graeme Malcolm, Elizabeth Marvel, David Morse, and Corey Stoll.

My personal favorite tale in this anthology is Hill's masterpiece, You Are Released, a tale of the coming nuclear armageddon witnessed by the passengers of a commercial airliner on it's way to Boston. This story is also included in Hill's collection of short fiction, Full Throttle.

The other stories vary in scope and levels of terror. Most listeners will likely be as surprised as I was to see the likes of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle on the contents page, as he lived the majority of his life in an era when flight was reserved for the imaginings of daydreamers. But the infancy of human flight came and went in the latter half of his life, and he was able to imagine and then author one of many terrible scenarios when man leaves the ground and skims the heavens. Fans of horror and suspense also will not pass up the opportunity to listen to tales by the likes of Matheson and Bradbury in the same anthology as well.

From the unmistakable voice of Stephen King, to the most excellent story by his son, to the inclusion of the ubiquitous zombie story by Bev Vincent, this one is highly recommended. I would especially recommend listening to it while many miles above the earth, trapped in a metal tube that somewhat resembles a coffin.